Efforts to preserve an ancient language, spoken for over 2,000 years, have led Iraq’s dwindling and conflict-battered Christian community to launch a new television channel.

Syriac, an ancient Aramaic dialect, has traditionally been used by Christians in Iraq and neighboring Syria, not just in homes but also in some schools and church services.

However, the number of Syriac-speaking communities in both countries has dwindled over the years due to decades of conflict pushing many to find homes in safer countries. The Christian population in Iraq is estimated to have decreased by over two-thirds in just over two decades.

“True, we speak Syriac at home, but sadly, I feel that our language is slowly fading,” said Mariam Albert, a news presenter on the Syriac-language Al-Syriania television channel.

The Iraqi government launched the channel in April to help sustain the language. With around 40 staff, the channel offers a variety of programming from cinema to art and history.

Albert, a 35-year-old mother, says, “It is important to have a television station that represents us.”

Most programs are presented in a dialect form of Syriac. However, Albert notes that the channel’s news bulletins are exclusively broadcast in classical Syriac, a form not widely understood by everyone.

The purpose of Al-Syriania is to “preserve the Syriac language” through “entertainment,” says Jack Anwia, the station’s director. “There was a time when Syriac was a widespread language across the Middle East,” he says, adding that Baghdad has an obligation “to keep it from extinction.”

“Iraq’s beauty lies in its cultural and religious diversity,” he adds.

Known as a cradle of civilizations, including the ancient Sumerians and Babylonians who produced the earliest known written legal code, Iraq is home to a plethora of cultures and religions.

Today, the country is predominantly Shiite Muslim but also houses Sunni Muslims, Kurds, Christians, Yazidis and other minorities. Arabic and Kurdish are the official languages.

Before the U.S.-led invasion in 2003, Iraq was home to approximately 1.5 million Christians. In the 20 years since, their population has dwindled to roughly 400,000, mostly residing in the north, following the brutal onslaught of the Islamic State group (IS) in 2014.

The Syriac language has been “sidelined,” according to Kawthar Askar, head of the Syriac language department at Salahaddin University in Erbil, Kurdistan Region. “We can’t say it’s a dead language… (but) it is under threat” of vanishing, he says.

Askar blames migration for the decline. Families who emigrate often continue speaking Syriac amongst themselves, but subsequent generations tend to abandon it.

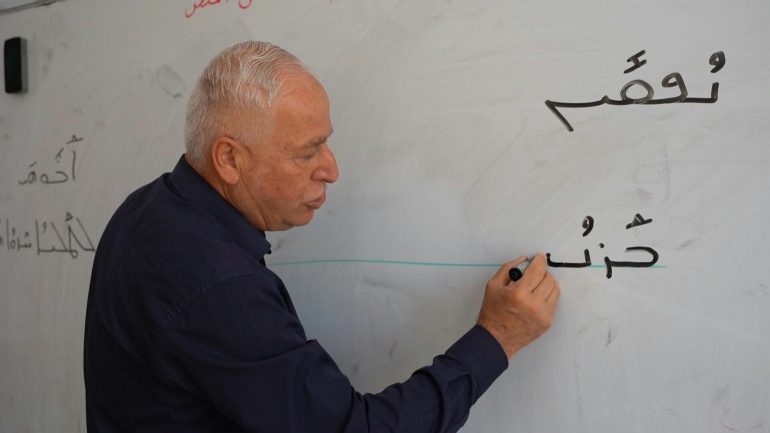

Syriac is taught at approximately 265 schools across Iraq, according to Imad Salem Jajjo, who is responsible for Syriac education within the education ministry.

The earliest written Syriac record dates back to the first or second century BC, reaching its peak between the fifth and seventh centuries AD. However, with the Islamic conquests in the seventh century, more people in the region began speaking Arabic, leading to a decline in Syriac by the 11th century.

Despite Iraq’s decades-long conflict, hundreds of Syriac books and manuscripts have survived.

In 2014, just before IS fighters seized vast areas of northern Iraq, the Chaldean Catholic archbishop of Mosul left the city, rescuing a collection of centuries-old Syriac manuscripts from the invading jihadists.

Approximately 1,700 manuscripts and 1,400 books — some dating back to the 11th century — are now preserved at Erbil’s Digital Centre for Eastern Manuscripts, which is supported by UNESCO, the United States Agency for International Development, and the Dominican order.

The conservation effort will “preserve the heritage and guarantee its sustainability,” Archbishop Michaeel Najeeb told AFP.

“Syriac is our history, it is our mother tongue,” says Salah Bakos, a teacher from Qaraqosh, a town near Mosul, that incorporated the language into its curriculum 18 years ago.

Bakos asserts, “Teaching Syriac is important, not only to children but all segments of our society… even if parents say it is a dead language that serves no purpose.”

AFP