In July, Bafel Talabani, leader of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), staged an impressive demonstration of military strength with the Counterterrorism Group’s (CTG) “largest ever” parade in Sulaymaniyah, just a day before a high-level meeting with the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP).

This rare parade aimed to showcase the PUK’s military capabilities, including its personnel and equipment. The notable presence of the contentious CTG head, Wahab Halabjayee—who an Erbil court has sentenced to death—alongside Talabani, sent a clear message to the KDP and his adversaries within the Green Zone, emphasizing his support for the beleaguered CTG chief. Interestingly, this show of power took place only two days after media reports about military forces in the Green Zone abducting a university professor, who was taken to the PUK forces’ Unit 70 HQ. The professor was released a day later, charged with photographing a security convoy.

These incidents exemplify the PUK’s approach to security and politics under Talabani’s leadership, and may dictate the Kurdistan Region’s trajectory in the near future. But how did we arrive here?

The Green Zone: A retrospective

For decades, both the PUK and the KDP have maintained their own paramilitary (Peshmerga) forces. Since the conclusion of the Kurdish civil war in 1998, both parties have held de facto military control over roughly half of Iraqi Kurdistan, informally known as the Green Zone and Yellow Zone, respectively (named after the parties’ political colors).

Following the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, the PUK and KDP strived to merge their administrations and formalize their Peshmerga and security forces in pursuit of legitimacy and Western support. Consequently, PUK’s Peshmerga forces were designated as Unit 70, ostensibly part of the Kurdistan Region’s Ministry of Peshmerga Affairs, but in reality answering to PUK leaders. Similarly, the KDP’s forces were designated as Unit 80.

The armed forces in the Sulaymaniyah/Green Zone region have traditionally been viewed as subservient to the PUK, and have been used for political ends, even allegedly involved in isolated instances of journalist assassinations.

However, despite these significant caveats, and notwithstanding the influence always held by PUK generals and military officials, the Green Zone has remained relatively tolerant of independent media, opposition parties, and civil society. In contrast, the KDP maintains a firmer grip on the Yellow Zone, allowing less room for dissent, opposition, and free press.

Though this may well be damning with faint praise, the limited freedoms granted by the PUK are uncommon sights in modern Iraqi history and markedly better than the rival Yellow Zone. Nevertheless, with the rising focus on the PUK’s military prowess, there are now fears that the suppression of dissent in the Green Zone is on the up.

What changed?

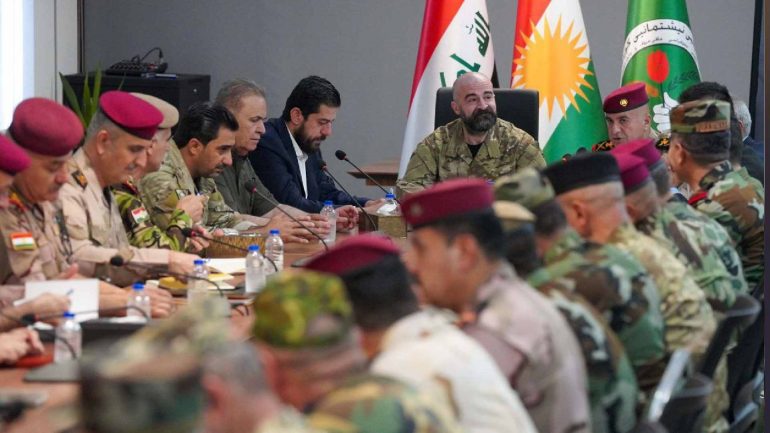

Since ousting his cousin, Lahur Sheikh Jangi Talabany, from the party’s co-presidency in 2021 and assuming the role of the de facto sole president of the PUK, Bafel Talabani has increasingly utilized military force to solidify his control over the Green Zone and negotiate with other political entities. The clash with Sheikh Jangi Talabany peaked on July 11 of that year, when Bafel installed a close ally at the head of the PUK’s influential intelligence (Zanyari) agency, a position previously held by Lahur. To illustrate the extent of this shift, Talabani has made public appearances with the CTG leader, Wahab Halabjayee, more than 20 times in the past year alone. His distinct military uniform has been a frequent sight at meetings with party leaders and diplomats, and he has explicitly threatened other parties on several occasions.

However, these changes are more than mere posturing. There has been a significant shift in the application of force in the Green Zone:

A series of assassinations have targeted individuals close to the ousted PUK co-leader, Lahur Talabany. For example, a PUK commander and his two bodyguards were killed in November 2021. An exiled CTG colonel was assassinated in Erbil in October 2022, with the KDP-controlled Kurdistan Region Security Council (KRSC) directly implicating the PUK’s CTG in the terror attack. Just two months ago, a key witness in the initial assassination of the first commander was also mysteriously killed.

Beyond the military clashes within Sulaymaniyah city between forces loyal to Lahur and Bafel, which resulted in gunfire exchanges during the struggle for PUK control, Bafel Talabani has allegedly used violence, or the threat of it, to impose his will since consolidating power. Evidence of this includes CCTV footage of a commander allied with Lahur being forcibly abducted, a raid on Lahur Talabany’s farmhouse with occupants detained on “illegal drug and firearm possession” charges, and the forceful seizure of party property from those associated with Lahur.

While crackdowns on protests are not new to the Green Zone, recent responses have been more severe and pre-emptive. Notably, multiple activists were reportedly arrested in advance when the opposition New Generation Movement (NGM) tried to organize protests. Political forces across the Kurdistan Region actively impeded journalistic coverage of these events, with the Kurdish journalists of Voice of America (VOA) detained and their equipment and phones confiscated. The Metro Center for Press Freedom reported that 2022 saw a record number of violations against journalists, with the PUK second only to the KDP in terms of such crackdowns.

Security forces in the Green Zone are now expanding into areas previously outside their reach. PUK’s commando units, known to be closely associated with Bafel, have begun distributing oil to impoverished families and providing “humanitarian aid” to schools. The trend of armed forces infiltrating more aspects of life, forcing the region’s most vulnerable groups to rely on them, is deeply concerning.

In a move reminiscent of other authoritarian leaders in the region, Talabani is increasingly courting Islamists and conservatives to widen his base in Sulaymaniyah. This strategy includes meeting with ultra-orthodox and controversial Islamist figures like Abdullatif Ahmed and personally, and performatively, closing down nightclubs without due process in an effort to “reclaim Sulaymaniyah,” as he phrased it. In June, an LGBT rights group was even forced to close in Sulaymaniyah as a concession to conservative politicians.

Driving forces

Beyond Talabani’s personal inclination and long-standing media portrayal as a “military man,” several structural factors have catalyzed the present trend.

The paradox of Peshmerga reform

Western powers have called for Peshmerga reforms for decades. This was formalized in 2016 when the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and the US signed a memorandum of understanding to cooperate in combating the Islamic State (IS). Several European countries have also backed and called for these reforms, leading to what has been described as the “unification” of the forces. Progress has been made, albeit at a slower pace than expected.

Following the territorial defeat of IS in 2017, and with its ability to launch attacks both within and outside Iraqi borders significantly reduced, the Western anti-IS coalition increased its focus on Peshmerga reforms, even linking them directly to aid and diplomatic support.

These reforms aim to depoliticize the Unit 70 and Unit 80 battalions, integrate them into the Ministry of Peshmerga Affairs, and make them solely accountable to the ministry. However, as Mera Bakr noted in a 2021 policy paper, these reforms overlook the region’s main security actors, the partisan Interior Forces.

Born from revolutionary militias fighting against Iraq’s Baathist regime, the forces of both the PUK and KDP retain their paramilitary characteristics, with the distinction between the Peshmerga (military) and the Asayish (internal security) often being blurred or virtually non-existent.

When the Coalition called for security sector reforms, the reclassification of 50,000 Peshmerga units as “internal security forces” by the PUK and KDP seemed a mere bureaucratic maneuver. Yet, while the exact impact is unclear and likely minimal, the Peshmerga reforms have politically weakened some traditional Peshmerga commanders, favoring the rise of emerging leaders within the parties’ respective intelligence services, such as Parastin and the CTG, who operate with more impunity, hence increasing their political influence.

Showmanship

Relations between the KDP and PUK have worsened over the past two years due to disputes in Baghdad and the Kurdistan Region over issues such as security, revenue, and election reforms. When a former CTG colonel linked to Lahur Talabany was assassinated in Erbil, and the KDP accused the PUK’s CTG of the crime, it had substantial political repercussions. The PUK has vehemently denied all the charges.

One significant outcome was the KRG, predominantly controlled by the KDP, stopping payment of CTG’s salaries and even demanding that the CTG’s leader, Wahab Halabjayee, surrender to an Erbil court. In response, Bafel Talabani enhanced Halabjayee’s status and importance as a pointed snub to the KDP.

Assessing the CTG’s exact role in the Green Zone’s military complex can be challenging. Is their prominence a reflection of their genuine importance to Bafel Talabani’s agenda, or is it just typical party politics common in the Kurdish political landscape? It’s difficult to ascertain. The recent military parade, described as the “biggest ever” and held on July 9, was interpreted by some as a response to media reports suggesting Talabani might surrender Wahab Halabjayee to the KDP in exchange for political concessions.

Foreign Policy Shifts and Internal Struggles

Since taking the sole leadership role in 2021, Talabani’s tenure has witnessed significant changes in the party’s foreign policy approach. Noteworthy events include a steadfast allegiance to the pro-Iran Shiite Coordination Framework (SCF) (the current Iraqi cabinet is backed by SCF factions), and apparent closeness to pro-Iranian militia figures like Rayan Al-Kildani and Qais Al-Khazali. Furthermore, joint operations between the CTG and Syrian Democratic Forces’ YAT, as well as Talabani’s provocative statements against Turkey, have led to the closure of Turkish airspace to all flights serving Sulaymaniyah airport.

These developments indicate a considerable shift in PUK’s foreign policy. Rather than maintaining strategic ambiguity, which previously allowed the PUK to leverage regional actors to its advantage, under Talabani’s leadership, the party seems to have taken a side.

Whether this change is due to the Green Zone’s financial and political challenges, the US’s gradually diminishing presence in the Middle East, or Iran’s alleged support for Talabani in his leadership struggle against Lahur Talabany, these dynamics have emboldened Bafel’s actions within the Green Zone. While the PUK’s strong Western ties and ongoing obligations remain, the durability of this relationship is uncertain.

Historical context

To fully understand the militarization of the Green Zone, it’s crucial to avoid the pitfalls of recency bias. The region has a long history of direct interventions by the PUK’s armed forces in civic and economic affairs. Thus, the question arises: how much has truly changed compared to the past couple of decades?

Rewind to the leadership struggle

After Jalal Talabani, the former PUK leader, fell ill and withdrew from politics, a power vacuum emerged within the PUK. From 2012 to 2017, conflicting statements from PUK leaders were commonplace as they accused each other of past mistakes, corruption, and favoritism.

The crisis peaked in September 2016 when senior PUK members Kosrat Rasul and Barham Salih proposed a new decision-making body within the party, claiming it was necessary to “correct its course.” This move effectively split the party into two factions: one led by late Jalal Talabani’s wife Hero Ibrahim Ahmed, his nephew Lahur Talabany, and his son Bafel Talabani; and another consisting of PUK veterans disgruntled by the Talabani family’s dominance.

Despite the internal strife, the Talabani family managed to maintain control over the party’s leadership, primarily due to their control over the party’s finances and their influence within the party’s intelligence agency, combined with the discord within the Rasul-Salih faction. The events of October 2017 underscored Bafel and Lahur’s control over the PUK Peshmerga, much to the dismay of many traditional PUK leaders. Following the Battle of Kirkuk in the aftermath of the ill-fated Kurdistan independence referendum, PUK forces pulled back to avoid confrontations with Federal forces, surrendering control of the city. This action was roundly criticized by many prominent PUK leaders, who labeled the conduct of their party’s forces as a “betrayal”.

The notable exceptions were Lahur Talabany and Bafel Talabani. While they did not explicitly take responsibility for the peshmerga withdrawal from the province, they defended the “independent decisions made by field commanders.” Furthermore, they pointedly blamed the PUK’s old guard for allowing tensions to escalate to such an extent with the Federal Government.

This event provided a stark demonstration of who truly held the reins of the PUK forces in practice.

The emergence of Lahur Talabany

Lahur Talabany, who started his political career by establishing the CTG in 2002, closely tied his early political life to the organization. When he assumed the position of head of the PUK’s Intelligence Agency (Zanyari), one of his first actions was to incorporate the CTG, then led by his brother Polad, into Zanyari. This merger significantly broadened the power of the force.

As the leadership struggle unfolded, Lahur Talabany heavily leaned on and boasted about his position as head of Zanyari. In response to claims from Rasul and Salih that the Talabani faction controlled the party’s security apparatus, Lahur Talabany argued during a televised phone call, “When you can’t pay salaries, the only thing you can be proud of is our security apparatus. Political parties shouldn’t intervene in the security agencies.”

Although the head of Zanyari is technically appointed by the KRG, in practice, it has always been a PUK-held position. Lahur Talabany’s assertion that political parties ‘shouldn’t intervene in security agencies’ suggested that he and the forces under his command would not obey the party’s decisions if led by Rasul and Salih.

New faces, new strategies

As Lahur and Bafel Talabani, the two cousins, gradually became the primary representatives of the PUK, a new generation of leaders, predominantly from the military, rose alongside them. Many traditional figures within the PUK were pushed aside during this transition.

Azhi Amin, the nominal head of Zanyari, and GTC’s Halabjayee, were practically unheard of before 2017. Interestingly, Halabjayee’s first high-level appearances occurred in 2017, alongside Polad Talabani, the then-head of CTG.

Throughout 2017 and 2018, it became increasingly evident that Lahur and Bafel Talabani were the central decision-makers in the PUK, despite not holding executive positions. Unprecedented in recent PUK history, their informal networks, financial prowess, and security affiliations granted them legitimacy, not the party apparatus. This shift was so stark it became a running joke in the Kurdish media. As late as mid-2019, Bafel Talabani would appear on television, introducing himself as a “low-level member of the PUK,” despite essentially controlling the party’s decision-making. A famous, often-repeated slogan of his at the time was “I’m not a politician.”

Maintaining control in a shifting political landscape

Despite the election of ‘not-politician’ Bafel Talabani and cousin Lahur Talabany as co-presidents of the PUK in 2020, PUK institutions never formed the basis of their legitimacy. Instead, the party adapted to reflect ground realities, resulting in widespread changes to the party’s key positions and bylaws.

This transition led to a delicate balance of power within the PUK, with Bafel and Lahur Talabani at the helm. Numerous analysts have noted that the CTG continues to underpin Lahur Talabany’s influence even after the establishment of the co-presidency.

Rising to the top

The exact reasons behind Bafel Talabani’s ability to depose Lahur Talabany as co-president and proclaim himself the sole leader of the PUK remain murky. Speculation suggests that disputes between Lahur Talabany and key CTG personnel allowed Bafel Talabani to assert his dominance. Regardless of the cause, the result is clear: Bafel Talabani is now the unchallenged—and perhaps only—decision-maker within the PUK.

Unrestricted by PUK’s intra-party institutions and no longer needing to share power with the former co-leader, Bafel Talabani used all available means to consolidate his control over the Green Zone. This included strengthening military forces such as the CTG and commando forces, who are directly accountable to him, over other party and government institutions.

Liloz Ibrahem Ahmed, Bafel Talabani’s favorite aunt, reportedly summed up the past decade’s events in the PUK with a comment aimed at Lahur Talabany after his dismissal: “Whoever is proud of his weapon stockpiles, military personnel, and militias will suffer a similar fate to that of Ashraf Ghani, the Afghanistan president. He was issuing threats yesterday, and he surrendered today.”

Additionally, the PUK has recently reformed its internal regulations to consolidate power under a single leader, ahead of its second conference since the late Jalal Talabani’s death. The trajectory appears evident: Bafel Talabani is seeking to legitimize his consolidation of power.

What lies ahead?

Forecasting future events in Iraq is notoriously difficult given the country’s dynamic and often volatile political landscape. However, a recent incident involving the Change Movement (Gorran) may offer some insight into the Green Zone’s potential future.

On March 19, just two days before the Kurdish New Year of Nawroz, Gorran leaders met with Lahur Talabany at their offices. The statement issued after the meeting by Gorran consciously avoided highlighting Lahur Talabany’s political status (he still insists on his PUK co-presidency title, rejecting the legitimacy of Bafel Talabani’s ‘coup’).

Within hours of the meeting, multiple local media outlets reported that the PUK leader was incensed with Gorran for meeting the former co-leader. Under significant pressure, Gorran issued a public message the next day to Talabani, explicitly addressing him as the PUK’s president and extending Nawroz greetings.

This episode might hint at the extent of political freedoms tolerated within Bafel Talabani’s Green Zone. With his control over the region’s military and economic sectors tightening and no internal challenges to his authority within his party, the prospects for democratic change appear bleak. His successful consolidation of power, coupled with an absence of real intra-party opposition, paints a grim picture for the Green Zone’s future under his leadership.